Written by Pilar Maestre

I am Pilar, currently 22 years old, and I have lived most of my life in Spain, where I was born. Recently, I volunteered for this association, without anticipating that they would ask me to write about the role Duchenne disease plays in my life, but I must say that it has turned out to be a surprisingly therapeutic experience.

My older brother is now 25 years old and lives with Duchenne. According to statistics, he has already surpassed half of his life expectancy. Although this is a terrifying thought, I don’t see him scared, I am, however, but thanks to him and his defiant attitude towards life and its obstacles, I am learning how to transform frustration into motivation.

Not long ago, I began realising the severity of this disease. Since I was little, I saw my brother walking on tiptoes and using his torso to get up from the floor, but I never thought it was something strange. It was only when other children started asking questions about him, and as the symptoms became more evident, that I realised that despite living with the disease, I lived quite disconnected from it and for the first time, I found myself asking the same questions as those children.

Fitting in

My brother and I have always attended the same school, my most vivid memories of this time are during my adolescence when I was about 13 years old, and my brother 16. At this time, simple things like walking, climbing stairs or bending down inevitably began to pose a challenge for him, so adapting to the new needs, the new family acquisition that year was an electric scooter. This scooter, so real and tangible, was like a reflection of the disease for me, exposed and making it harder to achieve the only thing you want as a teenager – fitting in, both for him and for me.

At 13, I didn’t fully understand what my brother suffered daily. Sometimes I focused only on myself and how people looked at me when I drove the scooter to the curb, I wanted that journey to be short and fast; I felt uncomfortable, and sometimes I wasn’t aware of how my brother must have felt nor fully understood the situation. As a result I didn’t always handle it well. It clearly didn’t leave me indifferent, but back then, I had typical concerns of my age and didn’t want to draw attention, or at least not like that.

The discomfort of others

And why not? Well, it’s simple. It is because I noticed people’s discomfort, a discomfort that I have realised often ends up expressing itself in one form or another of rejection, of evasion. This is clear to me, for example, when speaking to my brother, people address me instead of him directly, as if there was an issue with his soul rather than a physical one. Ironically, it’s this rejection, born out of misunderstanding, that can hurt more than the condition itself. They don’t want to face someone “condemned” to live in suffering, as if it were intrinsically his only possible way of living, ignoring that through this suffering, he not only lives but knows how to live.

This is something I have learned directly from him over the years, watching him take control of his life, set goals, and face life with courage, but when I was a teenager, I still had much to learn, although I always knew that him being in a wheelchair didn’t change who he was as a person. The human being is always the same, whether walking or rolling; there are no physical differences there.

In our daily lives, details became crucial, obstacles started to appear where there were none before. Since they were new, I only focused on the problems; my parents took care of the solutions. We were learning to live differently, more calculated, more planned, with a new perspective on what was now really important to us. When they started renovating the house, widening doors, building ramps, I saw it as exaggerated and unnecessary, a new front had opened, and I was invaded by fear of the unknown. I chose to avoid the situation, but inevitably, this period of ignorance did not last long.

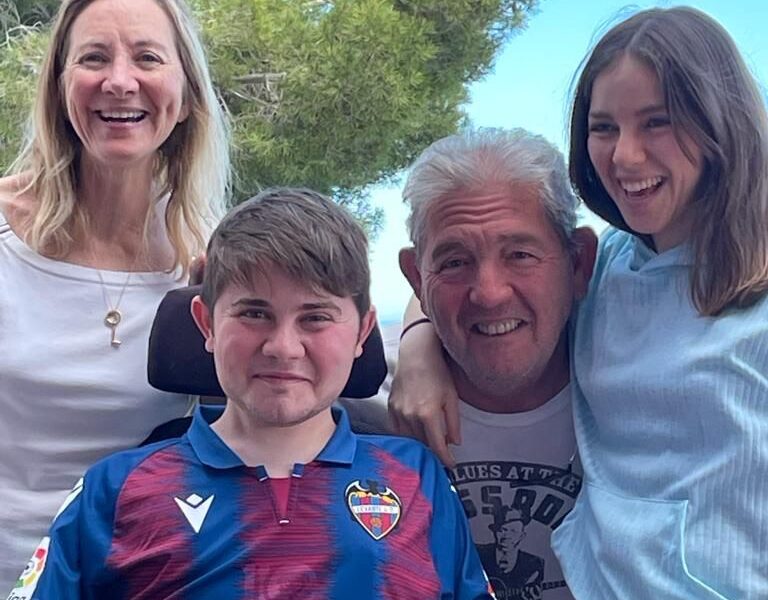

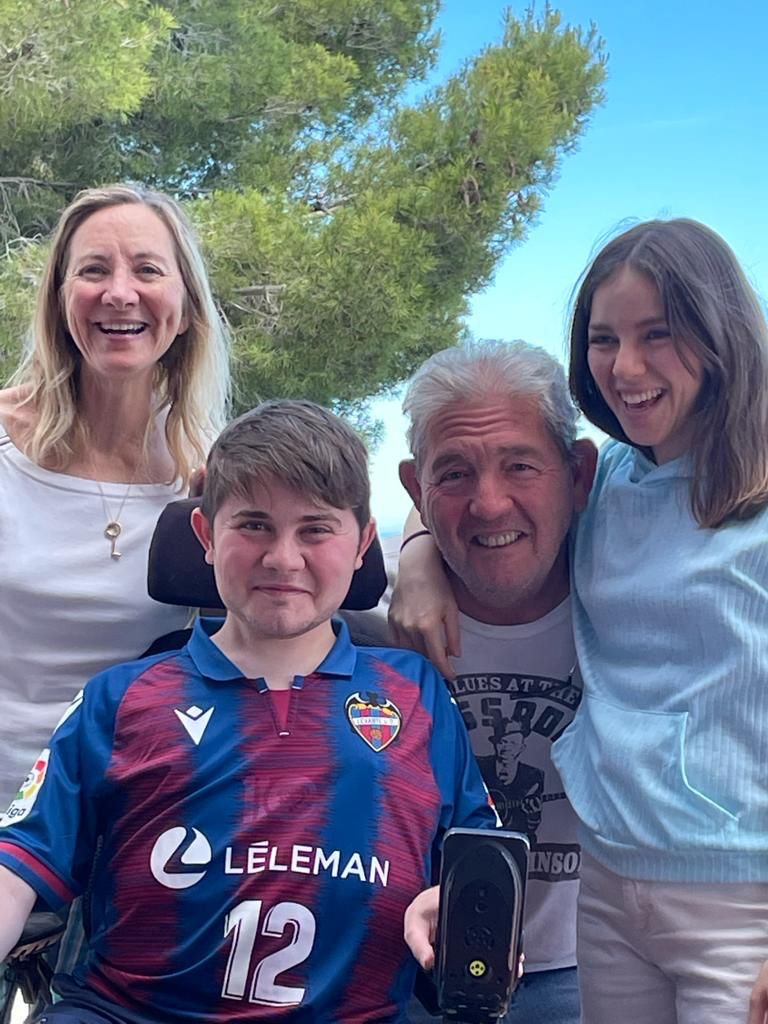

There was also the anguish that the wheelchair would isolate him, which happened partly inevitably because, despite wanting to ignore it, the wheels were a limitation. Every interaction with a new person was a challenge, will they ignore or see beyond the wheelchair? Most of the time, it was the former, but when someone approached to talk directly to my brother, I felt indebted to them, for being able to see beyond, as if it were a favor instead of what it really was—a person-to-person interaction. When they didn’t address me to ask about him, when I wasn’t an intermediary in a conversation that never required it, the only normality was found within the four of us at home.

Later, my parents sent me to study away for a few years until high school when I returned home. During those years, the progression of the disease went unnoticed in my daily life, which I assume was their main intention in sending me away.

When I turned 17, I attended the annual Duchenne Parent Project conference in the USA with my family for the first time. Here, I realized that what I wanted to do was help, although I didn’t know how. Until then, I had only worried about my brother’s health, hadn’t delved further, and my mind could only focus on the present, still unaware of what the future would hold, but seeing so many affected children like him, I became curious to know more.

Shared Experiences

I still couldn’t understand the scientific explanations they gave, but I was surprised by the number of parents filling the room, with paper and pencil in hand, with a defiant, determined look, seeking to learn, these desires captivated by hope but born out of their own fear of the inevitable prognosis. I entered the room full of siblings with a knot in my stomach. They shared their experiences and concerns, and I found myself surprisingly identified with many of them. I wasn’t the only one who felt hurt when people looked weirdly at their brother for walking on tiptoes, for constantly falling, for searching for ramps on the sidewalks.

In that conference I found myself staring at other children, but not because I found it odd as it had often happened to my brother on the street, but because the signs I saw in those kids were so familiar to me that it was strange to see them in someone other than my brother. After all, it is a rare disease. The other families and mine, were strangers to each other, but I could empathise completely and deeply with them, as if we were a reflection of each other’s emotions.

Everyone involved in this community had been fighting for a clear, immovable goal, and most importantly, a common one. That was the key point—the common effort among doctors, researchers, relatives, and patients gave them power, the power to act, fight, and, what´s best, it worked. Until then, I had only felt confused and powerless, but there I realised that something could be done, something worthwhile—the common fight against this disease. That’s what I decided to dedicate my life to.

Finding purpose

With this purpose in mind and fortunate to find my passion in science, I enjoyed studying Biotechnology in Valencia and focused on the research branch on neuromuscular diseases. My family primarily inspires me as they are the most important thing in my life, my greatest treasure. From my father, I learned the virtue of being fair, giving each thing the importance it deserves, and not giving up without trying first, from my mother, I learned to care for and dedicate myself to others, with love and affection, just as she does tirelessly every day, and thanks to my brother, I now know that one must live each day with the intensity it deserves, as the only truly certain thing in this life is the present moment.

We must not count life in years, but in moments, moments of joy, moments of happiness, moments worth remembering, those that will bring up a smile and get us through the harder times that will come by.

It’s true that living with this disease was not my own choice, but my attitude towards it is, so I am determined to continue educating myself to contribute in helping other families as well as my own, through this extraordinary field that is research.

I have been fortunate to work in several leading research centers on these types of diseases, and my next goal, always motivated by the desire to learn and develop in this area, is to pursue a doctorate focused on muscular dystrophies while continuing to contribute as a volunteer member of Action Duchenne and Duchenne Parent Project Spain. I attend the annual conferences of these associations and closely follow clinical trials and active research lines. Research progresses slowly, but it does progress, and it is essential to remind ourselves often to see the reality in its entirety, because despite how frustrating it sometimes is, there are reasons to have hope.

I approach my profession with determination and enthusiasm, determined to contribute to progress towards a cure, and being aware of how ambitious this goal is, I know that someday it will come. I am grateful to be part of this great community to which I owe so much, and which has given me so much more and I have reasons to trust that our efforts will not be in vain.

With Love,

Pilar

The most powerful stories come from lived experience. Would you like to write for us and share your story? The most powerful stories come from lived experience and we’d be honoured to share yours. Contact lizzie@actionduchenne for more information.

Previous Post

Previous Post